The trademark ‘Oh, my’ was met with thunderous applause as its speaker stepped onto the stage, hands raised high and fingers spread in the Vulcan salute.

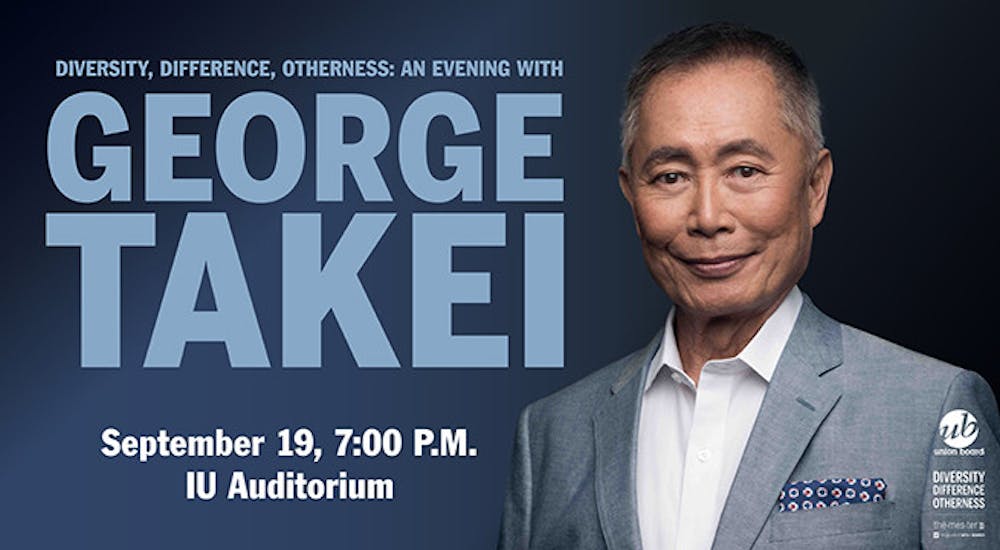

Actor and activist George Takei spoke September 19 at the IU Auditorium as part of the 2017 Themester. The talk, in a series along the theme of Diversity, Difference and Otherness, was co-sponsored by the College of Arts and Sciences, Union Board, the Media School, the Arts and Humanities Council, and the Office of the Vice President for Diversity, Equity, and Multicultural Affairs.

Takei began with his childhood, describing how he, aged five years old, and his family were forced into an internment camp with other Japanese-American families. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, E.O. 9066 was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, authorizing the imprisonment of citizens with Japanese heritage in ten camps across the nation. The citizens were labeled as alien enemies of the state.

“We were Americans, and yet hysteria and racism took over,” Takei said. “It was crazy – we weren’t aliens, and we weren’t the enemy.”

As a child, Takei said he did not fully understand what was happening, nor did he acknowledge the irony of reciting the Pledge of Allegiance – especially the line ‘with liberty and justice for all’ – in full view of a sentry tower and the barbed wire fence right outside the internment camp’s makeshift classroom.

A turning point came when the U.S. government realized the need for more soldiers to fight overseas, and, as a solution, presented the families imprisoned in the camps with a loyalty questionnaire. Takei related the survey’s most degrading question, number 28:

“Will you swear your loyalty to the United States of America, and foreswear your loyalty to the emperor of Japan?”

A ‘yes’ would mean there was loyalty to the emperor to be sworn, Takei explained, but a 'no' that there was no preexisting loyalty would apply to the first part of the question, as well.

“It was a no-win question,” Takei said.

Those who “bit the bullet” and answered 'yes' were allowed entry into the U.S. military, and served in a segregated unit, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, with the motto ‘Go for broke.’ These soldiers were fighting not just for American ideals overseas, but for freedom and respect on the home front, Takei said. After several successful missions, they returned home as the single most decorated unit of its kind throughout America’s history of warfare, and were greeted by President Harry S. Truman as heroes on the lawn of the White House.

“The war ended and, as suddenly as they rounded us up, the gates were opened,” Takei said.

The families had lost all their property and savings when they were interned, and were given $25 and a one-way ticket to a destination of their choice upon release. They had to rebuild their lives from there.

Takei spoke of how his own experience in his teenage years, seeking to understand the why behind the internment, led to more questions than answers as he found the same ideals repeated in history and civics books: liberty and justice for all.

“I couldn’t reconcile that with what I knew to be the reality of my childhood,” Takei said.

He said his father taught him what he knew about American democracy, that just believing in the ideals is not enough: one must be active.

“People make mistakes,” Takei said. “Democracy is dependent on people who cherish those ideals…and actively engage in that process to make that democracy work.”

Years of passionate social activism led to a breakthrough in 1988, when President Ronald Reagan issued an official apology on behalf of the U.S. Government to those Japanese-Americans who had been interned decades before.

“Democracy moves slowly,” Takei said. “But if we are actively involved, actively push…it bears fruit.”

He continued that, though the success renewed the faith of many in the efficacy of activism, there was still one area in which he felt he could not participate.

Since the age of ten, “I felt different in more ways than just my Japanese face,” Takei said.

But he had a promising career as an actor ahead of him, and, though he found comfort and relaxation in gay bars, he still felt the constant fear of being outed.

“If you wanted to be an actor, you couldn’t be known as a gay person,” Takei said. “I felt a constant, needle-prick anxiety.”

Then in the early 2000s, things began to change. In 2003, Massachusetts legalized same-sex marriage and became the first state to issue licenses to same-sex couples. Things were looking up, Takei said, especially as California, his home state, introduced a marriage equality act that passed through the legislature – only to be vetoed by then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Takei and his then-partner, now-husband Brad Altman, decided it was time for Takei to publicly voice his support for the LGBTQ+ movement, and his outrage at Schwarzenegger’s veto.

“We decided, ‘I’ve had an alright career,’” Takei said. “I’m gonna come out.”

A major victory for civil rights came in 2015 with the Supreme Court’s decision that all states must recognize same-sex marriage. Takei describes the joy he felt at hearing that decision, and his pride in “our America.”

“It was founded on shining ideals by great men,” he said. “But great men are also human beings, and human beings are fallible.”

Despite the pain caused in the past and the struggle that still faces the quest for equality, Takei assured the audience, “We are moving forward.”

He ended with a Q&A session, taking questions from Twitter that audience members were encouraged to send in during the show with the hashtag #TakeiTonight.

“We are living in interesting times, and I thank you for an interesting evening,” Takei concluded.